The Role of Religion

Religious organizations, primarily Christian denominations, played an integral role in developing the educational landscape in the Midwest. Indiana’s original 1816 constitution provided guidelines for establishing a free public education system, establishing elementary schools and secondary-level “seminaries” or high schools funded by local residents. However, no consistent oversight or funding made establishment practically non-existent. While local schools did appear prior to a new educational system adopted in the state’s 1851 constitution, which included creating the position of Superintendent of Public Instruction, many were private or still required tuition to attend.

Prior to the Disciples of Christ’s foray into organized education in Indiana, the Presbyterians (1827), Methodists (1837), Baptists (1837), Catholics (1842), and Quakers (1847) had already established schools, many of which also sustained preparatory or high-school level curriculums in addition to collegiate studies. These sectarian institutions—formally affiliated, funded, or run by a religious organization—traditionally taught based upon their denomination’s teachings.

The passion of the founders’ faith is evident in the University’s charter, where the institution’s objectives included “to teach and inculcate the Christian faith and Christian morality, as taught in the Sacred Scriptures, discarding as uninspired and without authority all writings, formulas, creeds, and articles of faith subsequent thereto.”

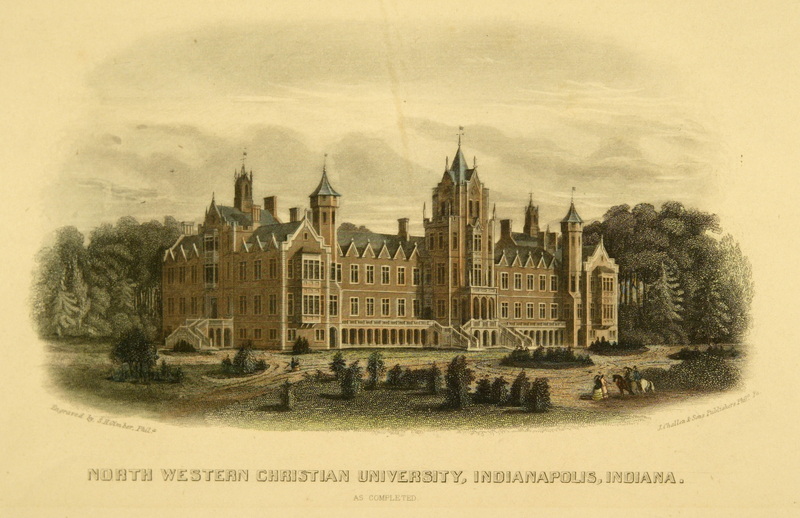

While North Western Christian University had a heavy religious influence—with the majority of its early presidents and faculty being in some way associated or connected to the Disciples of Christ Church—the institution was not a denominational school like many others in Indiana. The University was to be nonsectarian— not officially affiliated or under the control of a specific religious group—meaning that the Disciples of Christ denomination never officially operated or had any control. Students were required to take Christian-based classes, and while these courses were most likely founded in Disciples-of-Christ theology, the purpose was not necessarily to indoctrinate a specific way of thinking.

“May God grant that the University may not be thus a failure but that it may be perpetuated, strengthened and improved, a blessing and a benefactor to future generations and that ... this Institution may assist in diffusing the blessing and influences of a higher civilization, a more enlarged philanthropy and a purer Christianity.”

Ovid Butler to M. C. Tiers, Cincinnati, Ohio, on December 13, 1863

The Issue of Slavery

In the Antebellum era the issue of slavery confronted all Protestant denominations, and many denominations splintered into separate sects based on pro-slavery or abolitionist beliefs. The Disciples of Christ were no different. Many of the North Western Christian University founders—and to a large degree many of the Christian Church’s Hoosier members—held abolitionist beliefs. However, other members supported the opposite argument, including the prominent Disciples of Christ leader Alexander Campbell from West Virginia and Bethany College—the college he founded in 1840. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, divisions only increased. These opposing arguments varied from pro-slavery beliefs to a passive abolitionism that was against slavery as well as integration, instead supporting recolonization of enslaved people through the work of the American Colonization Society.